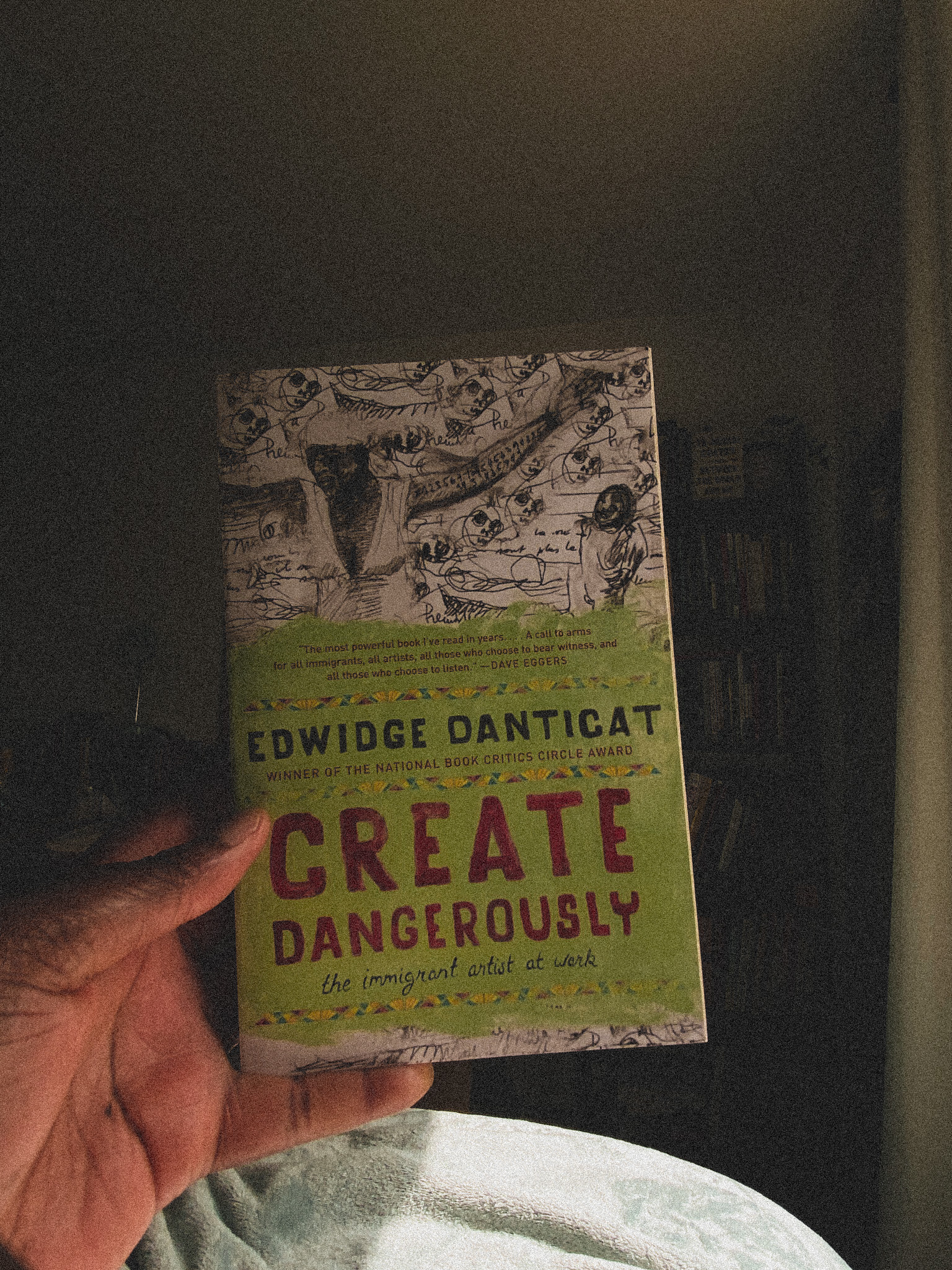

“Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist at Work” —Edwidge Danticat

In this memoir, Edwidge Danticat writes to honor the journey of the immigrant artist, beginning with defining a moment she calls her “creation myth” event, a public execution ordered by François “Papa Doc” Duvalier no November 12, 1964 in Port-au-Prince. Danticat spares no detail in this opening chapter as she describes the moment Numa and Drouin’s faces go from life to death and as their bodies follow suit, slumping down on the poles their bodies were held against.

She then makes a shift in the chapter to a discussion on creation myths, a term she uses to describe the moment when one becomes an artist, a moment that forms an obsession, a haunting. It was, like the story of Adam and Eve, “a heartrending clash of life and dead, homeland and exile involv[ing] a disobeyed directive from a higher authority and a brutal punishment as a result.” Disobeying the rules set up by the Duvalier regime, Numa and Drouin were also among many who left Haiti and returned, hoping to make a difference. As writers, they tapped into what it meant to create dangerously in a way that challenged the oppressive political regime of their time. They paid the price with exile: from this life into the next. Here are some of the many things Danticat writes as she describes the role of the immigrant artist through her life’s many fascinating stories:

“The immigrant artist must quantify the price of the American dream in flesh and bone.”

“The immigrant artist must sometimes apologize for airing, or for appearing to air, dirty laundry.”

“The immigrant artist challenges ‘historical amnesia’ and writes to overcome forgetting especially in honor of those ancestors who were “told to remove their past from their heads and dull their desire to return home.”

“The nomad or immigrant who learns something rightly must always ponder travel and movement, just as the grief-stricken must inevitably ponder death.”

An intense read, but for sure a worthy one.

Buy Here